Subtitles for the movies we make in our heads. Neurotechnologies are getting better and better at "reading" our thoughts, decoding what an individual means, and even what he thinks, but doesn't necessarily meanThe advances in these devices are such that they are no longer limited to deciphering verbal thoughts: some teams have already shown that it is also possible to "see" visual thoughts, that is to say, to guess the image a person is looking at.

A new study goes further, describing the content of videos we watch simply by analyzing brain activity. This new breakthrough, presented on November 5, 2025 in the journal Science Advances by a researcher from the Japanese communications company NTT, is not interested in verbal thoughts, but in visual thoughts, and could thus make it possible to decode the thoughts of subjects who do not master language, such as babies or animals.

An AI to describe the images we observe

This decoding relies heavily on artificial intelligence (AI) designed to describe a sequence of images, generating texts like those used to allow visually impaired people to enjoy a film. This language model is trained to progressively add words describing the elements of an image and how they interact. This method, called masked language modeling (MLM), predicts the missing words in a sentence, adding step by step all the necessary descriptions to get a good idea of what is happening on the screen. Then, these descriptions are translated into semantic features: for example, if we see a singer on screen, the semantic features could be "woman," "artist," "sing," etc.

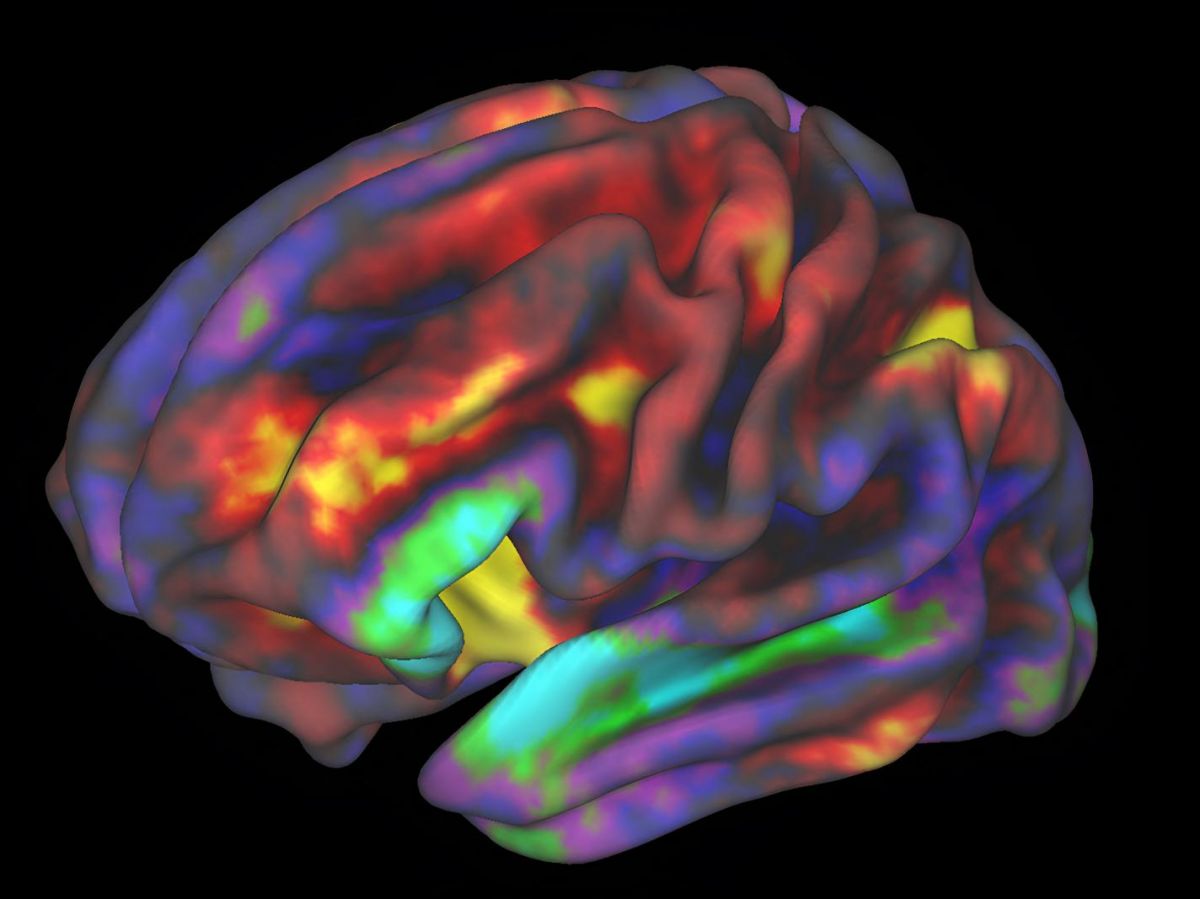

Simultaneously, the user views the same sequence of images, and their brain activity is recorded using functional MRI (fMRI), which analyzes blood flow in the brain and thus identifies which areas are activated in real time. The goal is to train the system to associate this brain activity with the semantic features linked to the observed images. This will then allow the system to infer the images the user is observing or imagining based on the semantic features associated with their brain activity.

"Reading" the brain to "see" the imagination

This method was tested on six participants, comparing descriptions generated from their brain activity while watching a video with those produced directly by AI from the same video. The aim was to determine whether these descriptions, extracted directly from the users' thoughts, could correctly guess which video they were watching (out of a total of 100 videos).

The success rate for some participants was around 40%, while the success rate due solely to chance (i.e., if the method didn't work) was calculated at only 1%. In other words, brain activity analysis was indeed able to partially extract descriptions that corresponded well to the video being watched, even if its effectiveness could be further improved. And it worked even when the participant wasn't directly watching the video but remembered it, showing that this technique could also allow us to guess what we imagine, not just what we see.

Predictions that do not depend on language

One might imagine that the generation of these descriptions in the mind uses language, and that the brain could translate what it sees into words to better understand it. Therefore, this method could simply be capturing the words the brain says to itself while watching the film. But that's not the case; these thought-generated descriptions were indeed due to visual thoughts, not verbal ones.

Two experiments support this conclusion: first, during the preparation period, when participants were in front of the screen getting ready to watch the video, they could read the AI-generated description text. However, the brain activity recorded at this time produced much less accurate descriptions than when they were actually watching the video. Second, analyzing only the brain regions dedicated to language did not produce descriptions as detailed as analyzing the entire brain, including regions crucial for processing visual information. In other words, it was primarily the mental images that allowed for the production of accurate descriptions.

This ability to "see" what the brain sees could be particularly useful for people who lack language skills, either due to an accident or illness affecting the region necessary for processing this information, or because the individual does not speak the language used by the method (English). The research article goes further and even suggests that this method could be used to decode the thoughts of babies or animals, bypassing language barriers.

However, the author also cautions that this method is only interpretive: it doesn't recreate a literal reconstruction of thought, but interprets it according to the language model used (and its biases). Thus, thought is filtered, in a way, so that it can be understood by AI. Finally, he raises a crucial question: what are the ethical risks of being able to access thought with simple fMRI scans, which are regularly used in clinical practice and research? He also emphasizes the urgent need to regulate these neurotechnologies to safeguard user privacy, ensuring that these "inner thoughts" remain hidden unless explicitly desired.