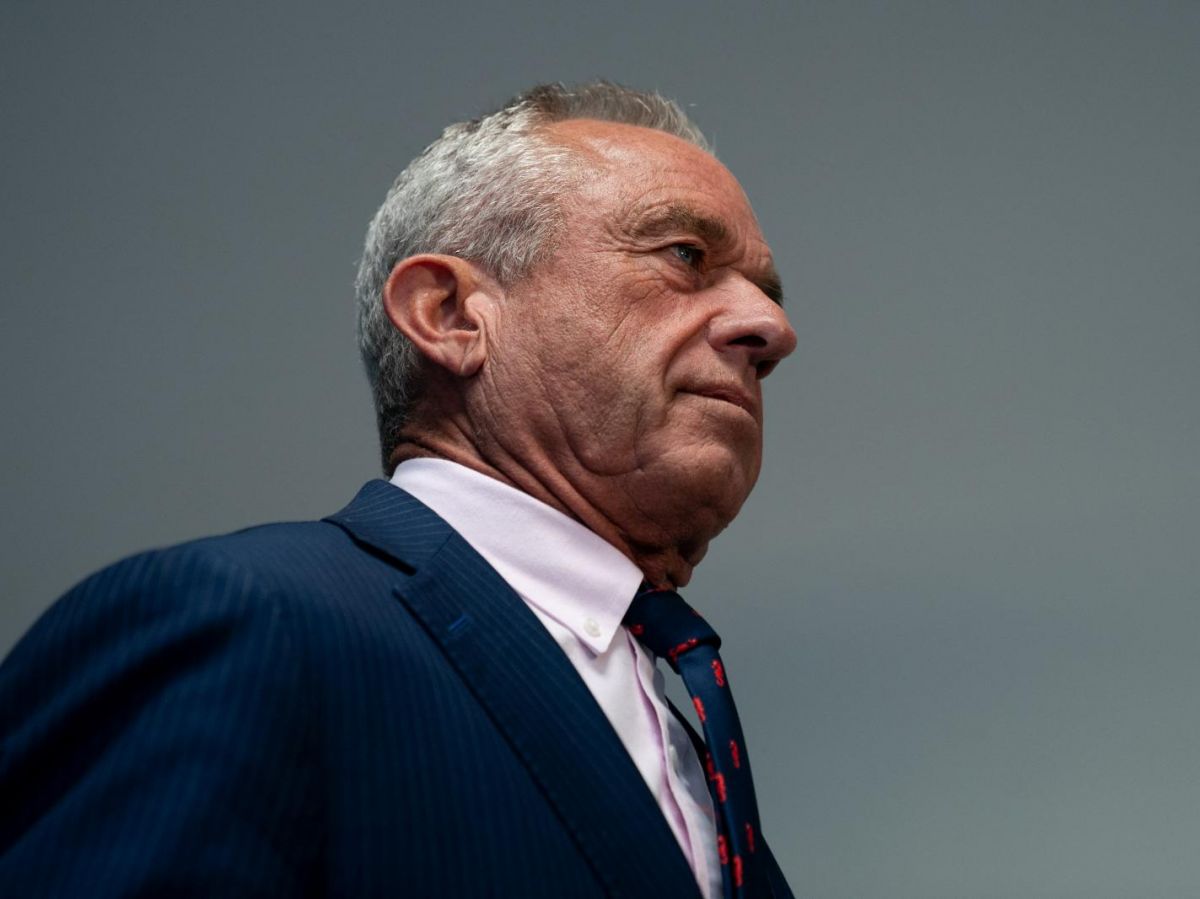

Atrial fibrillation, dysphonia, mercury poisoning leading to serious memory problems, the health report of the future Minister of Health in the Trump administration, Robert Francis Kennedy Jr., was scrutinized by the American media at the time when the latter was running as an independent candidate in the 2024 presidential elections. He then highlighted his relative youth and his "athletic" shape compared to the favorite candidates, Joe Biden and Donald Trump, aged 82 and 78 respectively (Kennedy Jr. is "only" 71). Hence the redoubled interest of press investigators in the past and present health of the nephew of the charismatic John F. Kennedy, President of the United States from 1960 to 1963: was he really that healthy?

THE New York Times reveals in 2024 an intriguing detail in a deposition of Robert Kennedy Jr. in the context of a divorce procedure dating from 2012: he claimed to have had neurological problems linked to the presence of a worm installed in his brain, which had allegedly "eaten part of it" and then died.

A parasitic worm in Robert Kennedy Jr.'s brain?

What was initially thought to be a brain tumor in Robert F. Kennedy was later diagnosed as a parasitic disease. Science and Future asks Rose-Anne Lavergne and Florent Morio of the Nantes University Hospital, both biologists at the Laboratory of Parasitology-Medical Mycology and Parasitic Immunology, they are circumspect about the elements reported by the American press. The most logical theory - and the most frequent - according to them, would be an infestation in Taenia solium after consuming infested pork.

What the American politician calls a "worm" lodged in his brain tissue is in fact the larval form of this parasitic worm. "The larva cannot transform into an adult worm in a human brain, it's impossible. It remains in the larval state and calcifies there," they explain.

Tapeworms that have taken up residence in humans

To understand why this larva came to nestle in Robert Kennedy Jr.'s brain, we must first understand the rather complicated life cycle of the tapeworm that parasitizes our intestines. We are what parasitologists call the definitive hosts of these worms belonging to the cestode class. In other words, it is in our intestines, and in no other animal species, that it can reach its adult form and reproduce. Three species of parasites are responsible for this disease, which is called human taeniasis (or tapeworm), and is mostly asymptomatic: Taenia solium, Tapeworm Or Tapeworm asiatica.

Before finding their final host, the larvae of these worms find their way into our intestines, using pork or beef as intermediate hosts. This includes all swine and bovine animals, but since pork and beef are common in our diets, it is these meats that we must be wary of.

The parasites are transmitted through infected human feces that come into contact with livestock feed in the context of poor water sanitation systems, or the use of human excrement on agricultural land, to name just a few common examples. The animal becomes infected by ingesting human fecal matter, which carries the worm's eggs. These metamorphose into embryos, migrating from the animal's intestinal walls to the muscles and organs such as the lungs, liver, eyes, or brain.

Read alsoIntestinal parasites that cause diarrhea were endemic in Jerusalem during the biblical period

A larva in the human brain, an incident!

Remember: the ideal place for tapeworms to become adults is in our intestines. Its juvenile forms primarily aim to reach this organ in our bodies. But sometimes, those of Taenia solium, the worm transmitted by pork, accidentally lands in other tissues. Humans can accidentally become the intermediate host. Contamination comes from outside through contaminated food or water. It can also be endogenous: "The eggs of an adult tapeworm can develop into embryos in the digestive tract of an infected individual, cross the mucosa, end up in the circulatory system and reach the smallest capillaries.", explain Rose-Anne Lavergne and Florent Morio. When these larvae infest other parts of our body and form cysts there, we no longer speak of taeniasis but of human cysticercosis, and in the brain, of neurocysticercosis.

That this tapeworm found its way into a human brain is nothing out of the ordinary. What's more unlikely is that this brain belongs to a citizen of a country with a food surveillance system that is efficient enough to generally keep these parasites out! Robert Kennedy Jr. probably became infected during a trip to South Asia, the New York Times in his May 2024 article.

What happens when a tapeworm larva settles in the human brain?

Between 2003 and 2012, when Robert Kennedy Jr.'s parasitosis was diagnosed, more than 18,000 patients were hospitalized for neurocysticercosis in the United States, the majority of them being of Hispanic origin. In France, according to Rose-Anne Lavergne, the diagnosed cases of cysticercosis or neurocysticercosis in France are, to her knowledge, exclusively imported cases.

The disease is far from harmless and painless when it affects the brain. Its symptoms can be multiple: headaches, intracranial hypertension, obstructive hydrocephalus, epilepsy, transient hemiplegia, encephalitis, stroke, cognitive disorders, etc.

Read alsoSnake-parasitic worm discovered in Australian woman's brain

Neurocysticercosis, off the radar?

In the geographical areas where it is endemic, it is a major public health problem with millions of sufferers. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 30% of epilepsies worldwide are the consequence of neurocysticercoses caused by these tapeworms in the larval stage, encysted in the central nervous system.

While taeniasis, cysticercosis, and neurocysticercosis seem to have disappeared from our radars in Western Europe and North America, the story of the "worm" in the brain of the new American Health Minister reminds us—is there any irony in this?—that these neglected diseases, according to the WHO classification, are still present in a large population worldwide and would benefit from mobilizing more resources for research and prevention.