A global decline in infections and deaths, effective prevention and treatment... The fight against HIV and AIDS is progressing, even if the end of the epidemic remains distant. State of play before World AIDS Day on Sunday.

– The disease is receding –

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections fell to their lowest level in 2023, between one million and 1.7 million, according to the annual report published Tuesday by the UNAIDS agency.

In the 2010s, the number of new infections fell by a fifth worldwide, according to another report which has just been published in the journal Lancet HIV.

Deaths, usually caused by opportunistic diseases when AIDS strikes in the late stages of infection, have fallen by about 401% to well below the one million mark per year.

This trend is driven primarily by a sharp improvement in sub-Saharan Africa, by far the region of the world most exposed to the AIDS epidemic.

The picture remains mixed, however, as infections are rebounding in other regions, such as Eastern Europe and the Middle East. We are far from the UN's objectives, which would like to virtually eradicate the epidemic by 2030.

– Effective tools –

One point is a consensus among HIV experts: preventive treatments, known as PrEP – pre-exposure prophylaxis – have become crucial in the fight against the epidemic.

Taken by people who are not infected but have behaviors deemed risky, they work very well to prevent infection.

Specialists are therefore pushing for their expansion. Thus, in France, the health authorities have just made it the highlight of new recommendations: PrEP should no longer be reserved for men who have homosexual relations.

"It's something that can be used by anyone who needs it at some point in their sexual life," stressed infectiologist Pierre Delobel during a press conference organized by the ANRS institute, which co-signed these recommendations.

People who are already infected have increasingly effective and practical treatments available, particularly because they need to be taken much less frequently.

– Obstacles remain –

However, the deployment of treatments – preventive or not – still faces many obstacles. This is particularly the case in poor countries, such as Africa, where the cost of medicines remains a problem.

According to UNAIDS, around ten million infected patients – around a quarter of them – do not have access to antiretroviral treatment, a therapy whose deployment has allowed countless people to live with the disease.

One case has fueled controversy in recent months. The Gilead laboratory offers a drug, lenacapavir, which promises unprecedented effectiveness, whether in prevention or treatment.

Experts say it could be a game changer, but the cost is astronomical – $40,000 per person per year.

Under pressure from those involved in the fight against AIDS, Gilead announced in early October that it would allow the low-cost production of its treatment by several generic laboratories, for the poorest countries.

The fact remains that the barriers are not only financial, especially for preventive treatments. It is also necessary to make people accept the idea of taking them without fear of being stigmatized, while behaviors such as homosexuality remain, in fact, unacceptable in many countries.

“The rollout of PrEP in Africa faces a major challenge: getting high-risk people to see and recognize that they are at risk,” summarized a 2021 article in The Lancet Global Health.

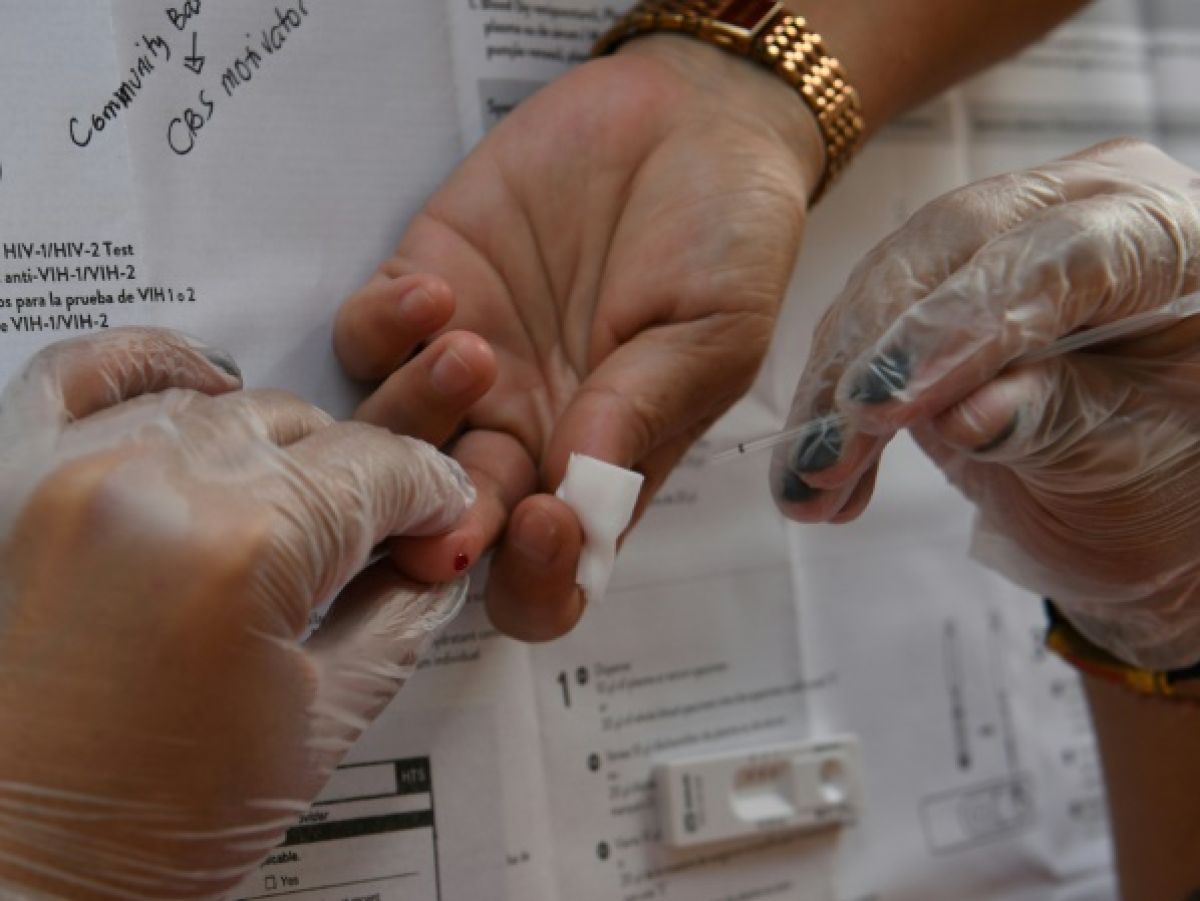

The problem is the same for screening, which is particularly important since many infections are detected at an already advanced stage, complicating their treatment.

– And the vaccines? –

Finally, some points are the subject of media attention that may appear disproportionate. For example, research on vaccines has not yet produced any conclusive results.

With the effectiveness of preventive treatments, "don't we finally have almost a vaccine?" asked infectiologist Yazdan Yazdanpanah, head of ANRS, at a press conference in mid-October, admitting however that "vaccine research must not stop."

Another development that should not be taken lightly is the few cases of remission observed in recent years: less than ten in total. While spectacular, they are the result of stem cell transplants, risky operations that are only possible in very specific cases.